With Midsummer only a day away, it feels apt to use this week’s Folkdays post to write something about the traditions and folklore associated with the summer solstice.

There were so many things I could have written about: whether it be beliefs, rituals, celebrations, or traditions. Yet, one story captured my imagination more than any other: the tale of The Oak King and The Holly King.

This story stems from pagan, particularly Celtic, mythology, yet it bears similarities to many other beliefs too. Read more about this story and these intriguing deities below!

In an earlier Folkdays post, I wrote a little about the idea of ‘comparative mythology’, which seeks to explain the similarities in folklore across varying cultures. The principal idea is that popular motifs, character archetypes, and narratives all have a common root in how early peoples understood the world: specifically, in their own image. Cosmic events, planetary bodies, and natural phenomena were imagined as living beings, with their own characteristics, motives, and actions.

One natural cycle which fascinated – and frightened – early peoples was the changing of the seasons. In the northern hemisphere, the light of summer and the dark of winter, encompassing the entire day in the northern-most parts of the world, influenced the way people lived, worked, thought, and felt. In order to understand it, mythologies arose which painted these alternating seasons as two distinct beings, vying for dominance throughout the year.

This post will explore the Celtic belief of The Oak King and The Holly King, but will also draw comparisons to myths in other cultures. Please note that the seasons, solstices, and equinoxes I refer to here are labelled with reference to the northern hemisphere; the direct opposite is the case for the southern hemisphere.

In all versions of the myth, The Oak King and The Holly King are men, though their relation to one another can vary. Sometimes they are presented as one man, who goes through a transformation twice a year; in other stories, they are two aspects of a single deity, two identities which fight to be the one in command. This deity is often taken to be the Horned God of Wiccan and Neo-Pagan belief: the Horned God himself is an archetype, bearing similarities to the Celtic Cernunnos, the Indian Naigamesha, the Greek Pan, and the Christian Devil.

In most instances, The Oak King and The Holly King are brothers, sometimes twins. The Oak King is the ruler of the summer, of light, fertility, and growth. The Holly King is the ruler of winter, darkness, and death. These brothers meet for battle twice a cycle, to fight for the Crown of the Year, and both times the one is dethroned as the other succeeds. When The Oak King takes the crown early in the year, the days are long, the crops grow tall, and new life is brought into the world; when The Holly King ascends towards the year’s end, long days are replaced by long nights, crops do not grow, and many living things perish in the cold.

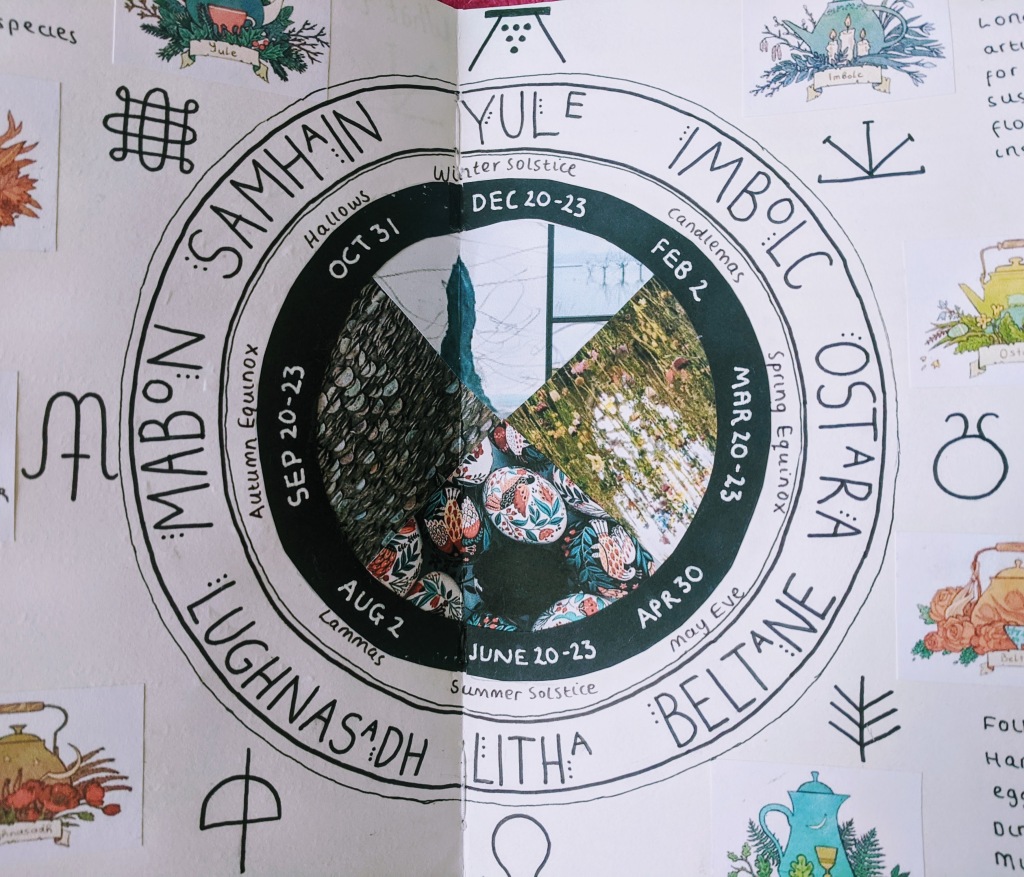

The lives, or the reigns, of the Kings are marked out by the eight Sabbats – holidays or festivities which occur at regular intervals through the yearly cycle. Two of these Sabbats fall on the equinoxes: Ostara on the spring equinox, Mabon on the autumnal equinox. Two sabbats fall on the solstices: Litha on the summer solstice, and Yule on the winter solstice.

The myth varies in that, in some instances, the Kings gain power on the solstices (Oak at Yule, Holly at Litha), snatching the crown when their opposition is at their strongest. This means that they start their reign in weakness, gradually ascending to strength, until they are deposed at the next solstice. In this telling, the Kings are reborn on their relevant equinoxes: defeated by The Oak King at Yule, The Holly King is reborn on Ostara, ready to take the crown back from his brother as his power peaks in the summer. The Oak King is reborn at Mabon.

In contrast to this, other traditions maintain that the Kings fight and gain the throne on the equinoxes. When we begin to see buds appearing, crops germinating, and animals breeding in springtime, it is a sign the Oak King has won the throne. He’ll steadily rise to full power by the summer solstice, before weakening until his defeat by The Holly King in autumn. This is when we begin to see the leaves turning browner, the nights getting longer, and the weather becoming colder. He’ll be at his full power in the dead of winter.

I can see the logic behind each version, though personally I find the latter to be more convincing, as it gives each King’s reign a rise to strength, before an inevitable downfall.

For that is the truth: the dethroning of each King is inevitable, just as the seasons are. Though his associations are death, darkness and cold, The Holly King should not be thought of as a villain, for he is needed just as much as his brother. Life could not bloom without death, and some creatures need the dark and cold to thrive. This story provides an interesting parallel between this myth and climate change. Humanity’s desire for the light, warmth, and comfort of The Oak King causes The Holly King to retreat, but the subsequent light pollution and global warming that ensues reveals the importance of balance, and the crucial role the cold and dark holds.

Moving on from the roles of these two Kings, to think instead about their associations: what is the significance of their names? Trees were sacred in Celtic belief, with many species of tree and plant having their own mythology and folklore. Oak and Holly were particularly special: the former for its strength, endurance, and versatility, the latter for its vibrancy and vitality all year around. The Oak became an association for summer, when the trees are in leaf and drown out the evergreens; the Holly became an association for winter, when they stand out, after all other trees have gone bare.

The Oak King, often represented as having a crown of oak leaves and acorns and dressed all in green, can be seen as comparable to the figure of The Green Man. The Green Man, like The Oak King, was seen as a figure of fertility, and is most commonly depicted as having a face made from sprouting oak leaves. This image of metamorphosis – from man into tree, or tree into man? – could tie in to the notion that the two Kings are the same being, transforming from one into the other.

The Holly King is likewise said to wear a crown of holly leaves and berries, dress in red, and sometimes as being accompanied by eight stags. This of course could arise from the belief that the Kings are aspects of The Horned God. But it also be connected to other figures, such as the Norse god Odin on his eight-legged steed, or Santa Claus and his eight reindeer (before the more modern inclusion of Rudolph). Due to Santa’s patchwork history, it is unlikely he is a direct descendant of The Holly King, despite his resemblances – though this could be another instance of comparative mythology at play.

Lastly, another way the two Kings are symbolised is through birds: The Oak King was associated with the robin, and The Holly King with the wren. To our modern minds, it might seem strange that the robin, which has long since become a staple of Christmas decorations, would represent the summer; similarly, it is odd that the wren, which used to be hunted and killed during festivities on Wren Day in December, would be a symbol for winter.

Myths abound regarding these two birds, and how they are seen in different cultures. Yet for me, I think there is a logic behind the linking of these birds with the Kings of Oak and Holly.

Cosmic cycles like the seasons were frightening for early peoples, before the causes of them were understood, measured, and taken as fact. In the depths of winter, it could seem like summer was never going to return. Capturing and killing a wren during midwinter could have been a way to banish The Holly King, and see about the end of his reign. Similarly, seeing a robin during winter was a sign that the Oak King, and summer, would return. Of course, both the robin and the wren can be seen during the summer months: a sign of The Oak King’s reign, but also a reminder that The Holly King is never very far away.

So this Midsummer, I would encourage you to go out in nature, find an Oak tree, and see if you can see The Oak King singing, high up in its branches.

I knew nothing of this myth before I stumbled across it, while researching Midsummer traditions! I am therefore very grateful to the following resources:

Top image: ‘The Holly King And The Oak King’ by Melissa A Benson

The Holly and Oak King from Stair na hÉireann

The Legend of the Holly King and the Oak King from Learn Religions

The Tale of the Holly King and the Oak King from Soul Body – provides a good timeline for what happens to the two figures on each sabbat

The Holly King and The Oak King from Emrys y Dewin – a good article for outlining the two figures and their correspondences

The Horned God – Oak King, Holly King and Green Man from Salem’s Moon – examines the interesting connections between the two figures and other deities

The Oak King and the Holly King from UU World – an interesting example of using this tradition as a parable for climate change

Winter Solstice – Robin and Wren from The Dreaming Path if you’d like to learn more about the mythologies behind these birds!

6 thoughts on “Folkdays: The Oak King”